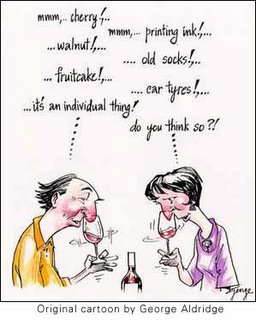

I’ve posted elsewhere on this idea of calibrating your palate to that of a wine critic. I’m not going to repeat that discussion here, but the dilemma is far from simple. Not only is it important to consider whether a wine critic’s description of a wine has meaning for you and whether you trust the critic to get his/her descriptors correct. But the biggest problem with this idea of calibrating your palate is that I have never seen any approach or description of the method that one would use to achieve it, beyond the glib advice to find a critic whose palate matches your own! How do you match palates? What aspects of the wine need to be compared? Are some aspects more important than others? How many of the individual aspects of a wine need to be identified by two tasters in order for a match to be achieved? How many wine critics should you try to compare with yourself?

I’ve posted elsewhere on this idea of calibrating your palate to that of a wine critic. I’m not going to repeat that discussion here, but the dilemma is far from simple. Not only is it important to consider whether a wine critic’s description of a wine has meaning for you and whether you trust the critic to get his/her descriptors correct. But the biggest problem with this idea of calibrating your palate is that I have never seen any approach or description of the method that one would use to achieve it, beyond the glib advice to find a critic whose palate matches your own! How do you match palates? What aspects of the wine need to be compared? Are some aspects more important than others? How many of the individual aspects of a wine need to be identified by two tasters in order for a match to be achieved? How many wine critics should you try to compare with yourself?I rarely see extensive comparisons of tasting notes from wine critics, so how do we even know that their palates are consistently different for accurate calibration to be attempted? Perhaps I shouldn’t be too adamant on this point. There seem to be endless comparisons between wine critic X with Robert Parker or vice versa.

Even so the idea that one wine critic may be more attuned to your tastes than any other can be tested in a rudimentary way by simply recording a tasting note and comparing it with said wine critics. In the interests of time and space I have selected a single wine in order to compare the description of four different wine critics to see what similarities, or differences, exist in the description of a wine. There is no reason why you can’t do this yourself with as many wines as you want.

The wine is Wayne Dutschke’s 2002 St Jakobi’s Shiraz (Barossa Valley).

My tasting note is from our visit to Dutschke Wines on December 13, 2004. I noted that the 2002 St Jakobi Shiraz was a dark cherry, and chocolate just exploded out of that glass! The wine had big rich blackberry flavors, but with a soft and elegant entry and wonderful balance. You didn’t have to wait around for the wine to hit your palate in bits and pieces; it was seamless, wonderfully integrated, with a lengthy finish (2, 2, 4.3, 10.5 = 18.8; 15% alcohol). For those who are counting an 18.8 out of 20 is a 94 on the 100 point sale.

The other tasting notes are:

Vibrant mix of black and red fruits, perfectly integrated vanillin oak and fine, ripe tannins. Elegant style. Rating 92. Drink 2012. James Halliday Wine Companion 2005.

…………..This wine is bang on the money: fruit expressive, laced with coffee oak but not excessively so, full of heart-felt blue and black and red berry fruit, and ripped with choc-mint flavour. If anything it’s a pass too heavy on both the mint and the alcohol-but its great drinking. Drink: 2004-2012. 91. Campbell Mattinson Winefront Monthly Collected Reviews 2002-20005.

…………….Layered and full-bodied, with notes of expresso roast, creosote, blackberries, currants, licorice, and pepper, this rich, full-throttle classic Barossa Shiraz can be consumed now and over the next 10-12 years. 92 points. Robert Parker, Jr.’s The Wine Advocate. Issue 155. (10-25-04).

Ripe and well shaped, with cherry, berry, plum, mineral and licorice that sail on. Just enough juicy acidity, with integrated oak and refined tannins. 94 Harvey Steiman. Wine Spectator October 15, 2005.

Now an initial run though these notes might see some saying that all reviewers find the wine to be excellent, so what is the problem? But this is not about the general assessment, or score, given to the wine this is about the description of the wine from aromas to taste. The description of aromas shows clear similarities and differences. The differences are Mattinson’s mint and alcohol, Parker’s currents, creosote, and pepper, and Steiman’s plum and mineral. Such differences in detection of aromas is not unusual among a group of tasters. Why such differences occur is not completely known. Some of the difference is physiological, that is, some people can smell better than others. But studies have shown that very few of us can smell more than a few aromas.

What about the other aspects of wine, its acidity and tannins? What about balance and integration of the components? Well again there are some similarities and differences. For me the wine is integrated as a whole, while Halliday and Steiman have integrated oak; oak is only a single component albeit an external one that does need to be integrated. In contrast I have an elegant entry, Halliday is more effusive calling the Dutschke an elegant style. These are very significant differences in the use of both integrated and elegant. Balance is only used once!

In truth all five assessments are quite different, although perhaps Steiman and Halliday are somewhat similar. But we come back to the real question. How do you choose one (or more) of these as a calibrator? For me I can only pick my own tasting note as the other four are too different from mine. The naysayers will argue that you can’t base the selection of a calibrator on just one wine. My question to these individuals is how many wines are enough? And what characteristics of the tasting note am I to base my selection on? I have a sneaking suspicion that if you rigorously compare tasting notes of multiple wine critics to your own for a number of wines you will continue to find differences and those differences will not be consistent.

1 comment:

I think that the greatest service a wine drinker can perform for themselves is to use tasting notes and scores from various wine critics as an "ideas list" only.

If you see several critics, or better still bloggers, giving a wine a bit of a wrap, then pick up a bottle and make up your own mind. If it is great, grab a six pack and move on to the next new and exciting wine to try.

Post a Comment